Multiple sclerosis isn’t just a neurological disorder-it’s an internal betrayal. Your own immune system, designed to protect you, turns against your brain and spinal cord. It doesn’t attack germs or viruses. Instead, it targets the protective coating around your nerve fibers, the myelin sheath. When that coating gets stripped away, messages between your brain and body start to glitch, slow down, or disappear entirely. That’s when numbness hits, vision blurs, or your legs feel like they’re made of lead. This isn’t random damage. It’s a targeted, ongoing assault by your immune system, and it’s happening right now in about 2.8 million people worldwide.

What Happens When the Immune System Goes Rogue

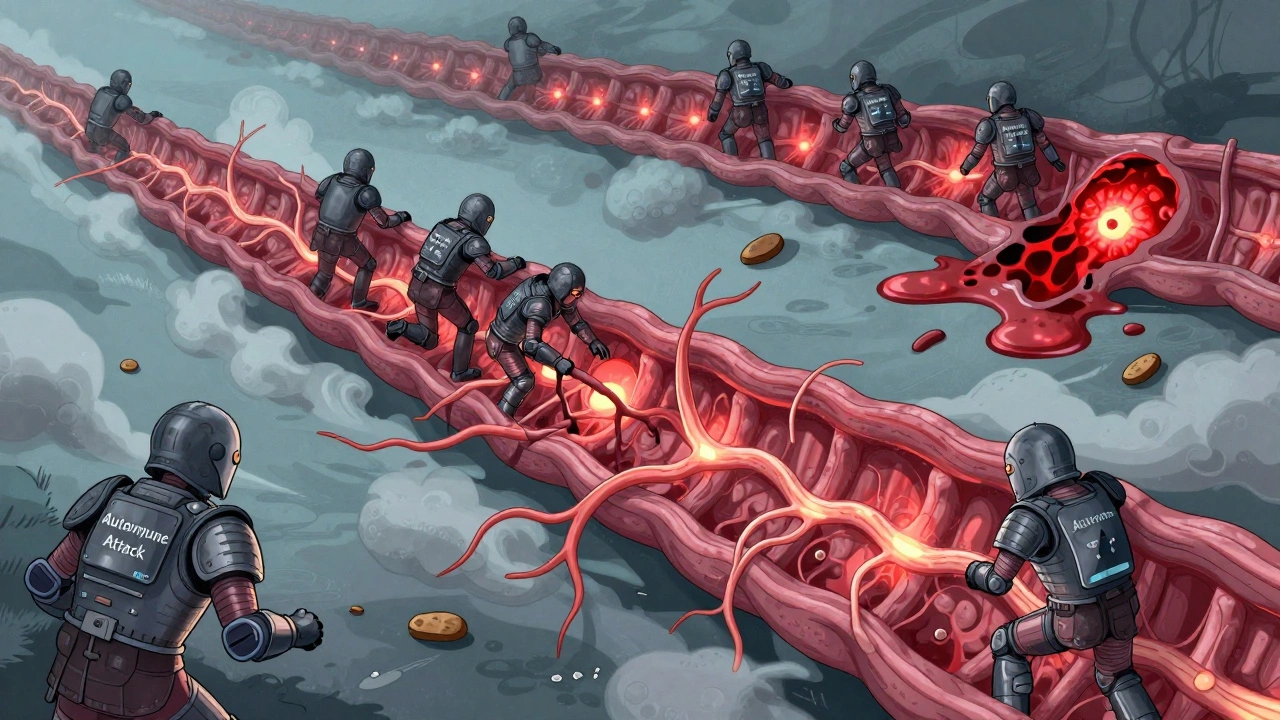

In a healthy body, immune cells like T cells and B cells patrol for threats. They remember invaders and strike fast. In multiple sclerosis, something goes wrong. These cells start seeing myelin-the fatty insulation around nerves-as a foreign invader. Why? No one knows exactly. But we do know it’s a mix of genes and environment. People with certain HLA gene variants are more at risk. And if you’ve had Epstein-Barr virus (the virus behind mononucleosis), your chance of developing MS jumps 32 times. Add in low vitamin D, smoking, or living far from the equator, and the risk climbs even higher. The real trouble starts when immune cells cross the blood-brain barrier. This barrier is supposed to keep harmful stuff out of the brain and spinal cord. But in MS, it leaks. CD4+ T cells, especially a nasty subtype called Th17, slip through. Once inside, they wake up other immune players: B cells, macrophages, microglia. These cells start producing inflammatory chemicals like TNF-alpha and interleukins. The result? Myelin gets chewed up. Axons-the actual nerve fibers-start to fray. And over time, scars form. These scars are called plaques or lesions. They’re the physical proof of the attack.The Four Patterns of Damage

Not every MS case looks the same. Scientists have identified four distinct patterns of tissue damage, based on what’s happening inside the lesions. Pattern I is mostly T cells and macrophages chewing through myelin. Pattern II adds antibodies-meaning B cells are actively making them. Pattern III is more complex: myelin-associated glycoprotein vanishes first, and oligodendrocytes (the cells that make myelin) start dying off. Pattern IV shows oligodendrocytes in distress, with no sign of repair. This matters because it tells doctors that MS isn’t one disease. It’s a group of related diseases with different triggers and progression paths. That’s why treatments work for some people and not others.What You Feel: The Real Symptoms

You don’t feel a lesion. You feel what it does. When the optic nerve gets attacked, vision blurs or darkens-sometimes overnight. That’s optic neuritis. When the spinal cord is damaged, you might feel an electric shock down your spine when you bend your neck. That’s Lhermitte’s sign. Fatigue? It’s not just being tired. It’s a crushing, bone-deep exhaustion that doesn’t go away with sleep. Eighty percent of people with MS live with it. Numbness? Tingling? Walking becomes a chore. Forty-two percent report trouble with mobility. These aren’t side effects. They’re direct results of myelin loss and nerve damage. The most common form-relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS)-hits about 85% of people. You get a flare-up: vision fades, balance goes, strength drops. Then, after weeks or months, things improve. But each attack leaves behind some damage. Over time, those small losses add up. Without treatment, half of RRMS patients need help walking within 15 to 20 years. With modern therapies, that number drops to about 30%. That’s the power of early intervention.

How Treatments Fight Back

Today’s MS treatments don’t cure the disease. But they stop the immune system from attacking as hard. Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are the backbone of care. Ocrelizumab, for example, wipes out a specific type of B cell-CD20+ cells-that fuel inflammation. In clinical trials, it cut relapses by 46% and slowed disability progression by 24% in primary progressive MS. Natalizumab works differently: it plugs the door. It stops immune cells from crossing the blood-brain barrier. It’s powerful-reducing relapses by 68%-but it carries a rare but deadly risk: progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). That’s why doctors test for the JC virus before prescribing it. Newer drugs target different parts of the immune chain. Some block specific cytokines. Others calm overactive T cells. The goal isn’t just to reduce flares-it’s to prevent long-term damage. And it’s working. People diagnosed today have a much better outlook than those 20 years ago.The Hope for Repair

The biggest question now isn’t just how to stop the attack-it’s how to fix the damage. Can we regrow myelin? Early trials say maybe. Clemastine fumarate, an old antihistamine, showed surprising results in phase II trials. It improved signal speed in the optic nerve by 35%, suggesting myelin was being rebuilt. Other drugs are being tested to wake up oligodendrocyte precursor cells-the brain’s own repair crew-and get them to do their job. This isn’t science fiction. It’s happening in labs in Boston, London, and now in Dunedin, where researchers are studying how inflammation blocks regeneration. Biomarkers are also changing the game. Blood tests for neurofilament light chain (sNfL) can now tell doctors if inflammation is active-even before symptoms appear. Levels above 15 pg/mL mean the immune system is still firing. That helps decide whether to switch treatments before more damage is done.

What’s Next

The field is moving fast. Researchers found that dendritic cells in MS patients are actively presenting myelin fragments to T cells, keeping the attack alive. That’s a new target. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs)-web-like structures released by immune cells-are now known to break down the blood-brain barrier. In 78% of acute relapses, these NETs are elevated. Blocking them could be the next breakthrough. The International Progressive MS Alliance has poured $65 million into research since 2014. Projects span 14 countries. The focus? Understanding why MS turns progressive. Why does the damage keep growing even when flares stop? That’s the holy grail.Living With MS Today

People with MS aren’t waiting for a cure. They’re living full lives-with adjustments. Physical therapy helps with balance. Medications manage fatigue and spasticity. Mindfulness and exercise improve quality of life. Support groups on Reddit and elsewhere give people a place to share stories: how they learned to walk again, how they kept working, how they dealt with the fear. The truth is, MS is unpredictable. But it’s no longer a death sentence. With early diagnosis, the right treatment, and ongoing research, many people live decades with minimal disability. The immune system may have turned traitor. But science is learning how to outsmart it.Is multiple sclerosis hereditary?

MS isn’t directly inherited like a genetic disease, but having a close relative with MS increases your risk. If your parent or sibling has it, your chance rises from about 1 in 750 in the general population to around 1 in 40. That’s because certain genes-like HLA-DRB1*15:01-make you more susceptible. But genes alone don’t cause MS. You also need environmental triggers like Epstein-Barr virus, low vitamin D, or smoking.

Can you get MS if you’re over 50?

Yes, though it’s less common. Most people are diagnosed between ages 20 and 50. But about 10% of cases are diagnosed after 50. Late-onset MS often looks different-it’s more likely to be primary progressive, meaning symptoms get worse steadily without clear relapses. Diagnosis can be harder because symptoms like balance issues or memory problems are often mistaken for normal aging. That’s why doctors now consider MS even in older adults with unexplained neurological changes.

Does stress cause MS flare-ups?

Stress doesn’t cause MS, but it can trigger relapses. Studies show that major life stressors-like losing a job, divorce, or the death of a loved one-can increase the risk of a flare-up in the weeks after. It’s not the stress itself, but how it affects your immune system. Chronic stress raises cortisol and inflammatory markers, which may lower your body’s ability to control the autoimmune attack. Managing stress through therapy, exercise, or mindfulness can help reduce flare frequency.

Why do women get MS more often than men?

Women are two to three times more likely to develop MS, especially in high-prevalence areas. The exact reason isn’t clear, but hormones likely play a role. Estrogen may boost immune activity, while testosterone might have a protective effect. Pregnancy, which raises estrogen, often reduces relapses-but the postpartum period carries a higher risk. Research is now exploring whether hormonal therapies could help manage MS in women.

Can diet cure or reverse MS?

No diet can cure MS. But what you eat can influence inflammation and overall health. Diets rich in omega-3s (like fatty fish), antioxidants (berries, leafy greens), and fiber (whole grains, legumes) may help reduce fatigue and improve gut health, which is linked to immune function. The Wahls Protocol and Swank Diet have anecdotal support, but no large studies prove they stop disease progression. Avoiding processed foods, sugar, and excessive saturated fats is wise. Always talk to your doctor before making major dietary changes, especially if you’re on medication.

Is exercise safe if you have MS?

Yes-and it’s one of the most effective tools you have. Regular exercise improves strength, balance, mood, and fatigue. Swimming, cycling, yoga, and tai chi are often recommended because they’re low-impact and can be adjusted for ability. Even short walks help. Studies show people who exercise regularly have fewer relapses and slower disability progression. The key is to listen to your body. Overheating can temporarily worsen symptoms, so cool environments and hydration matter. Work with a physical therapist who understands MS to build a safe routine.

Can MS turn into a different disease?

No, MS doesn’t turn into another disease like ALS or Parkinson’s. But it can change how it behaves. Relapsing-remitting MS often transitions to secondary progressive MS, where disability slowly worsens without clear relapses. This isn’t a new disease-it’s the same condition evolving. About 50% of RRMS patients develop this form within 10 to 15 years without treatment. Newer DMTs are now approved to slow this transition. Primary progressive MS, on the other hand, doesn’t have relapses from the start. It’s a different clinical pattern, but still MS.

Are MS lesions visible on MRI?

Yes, that’s one of the main ways doctors diagnose MS. MRI scans show areas of demyelination as bright spots (lesions) in the brain and spinal cord. These lesions appear in specific patterns-around the ventricles, in the brainstem, or along the spinal cord. The McDonald Criteria use lesion location, number, and changes over time to confirm MS. But not all lesions mean MS. Some can be caused by migraines, aging, or other conditions. That’s why diagnosis requires a full picture: symptoms, MRI, spinal fluid tests, and ruling out other causes.

What’s the life expectancy for someone with MS?

Most people with MS live nearly as long as those without it. On average, life expectancy is about 5 to 10 years shorter, mainly due to complications like infections, mobility issues, or swallowing problems in advanced stages. But with modern treatments, that gap is shrinking. People diagnosed today, especially those who start treatment early and stay active, often live full, long lives. The focus has shifted from survival to quality of life-keeping people moving, thinking clearly, and engaged in their lives for decades.

Can you get pregnant if you have MS?

Yes, MS doesn’t affect fertility. In fact, many women experience fewer relapses during pregnancy, especially in the second and third trimesters. That’s likely due to hormonal changes that suppress immune activity. But the postpartum period-especially the first three months after birth-is a higher-risk time for relapse. Planning ahead is key. Some disease-modifying therapies must be stopped before conception. Others are safe during pregnancy. Always work with a neurologist and obstetrician who specialize in MS to manage your care before, during, and after pregnancy.

14 Comments

Man, this post really laid it out. I’ve had MS for 8 years and honestly, the part about fatigue being bone-deep? That’s the one no one gets. I sleep 10 hours and still feel like I’ve been dragged through a gravel pit. But exercise? I do yoga every morning. It’s not magic, but it’s my lifeline. 🙌

This is just another pharmaceutical propaganda piece. They don’t want you to know that MS is caused by 5G radiation and glyphosate. The real cure is a 30-day juice cleanse and avoiding all modern technology. The FDA knows this but keeps it hidden because drugs are more profitable.

Let me tell you something-this isn’t just medicine, it’s a war. And science is finally arming us with the right weapons. Ocrelizumab? That’s not a drug, it’s a precision strike on the traitors inside your body. And clemastine? A forgotten antihistamine turning into a myelin superhero? That’s the kind of plot twist Hollywood can’t even dream up. We’re not just managing MS-we’re rewriting its ending.

Interesting. But I’ve read this before. The stats are solid but the tone feels overly dramatic. Why not just state the facts without the cinematic flair?

Of course Americans think they’re the only ones researching MS. In India, we’ve had Ayurvedic protocols for centuries that stabilize the immune system without toxic drugs. Your entire medical system is built on profit, not healing. Why are you still using MRI scans when our herbal decoctions have been reducing lesions since the 1970s?

Wait-so you’re telling me that a simple antihistamine like clemastine can rebuild myelin? And you’re not screaming this from the rooftops? The pharmaceutical industry is actively suppressing breakthroughs that don’t require lifelong prescriptions. This is a scandal. Someone needs to file a whistleblower report.

Did you know the CIA created MS to control the population? The myelin damage? That’s just a cover for nanotech implants they put in your spinal fluid during flu shots. The real reason they’re pushing MRI scans is to map your neural activity. They’re watching you. And yes, Epstein-Barr? That’s a bioweapon they let loose in 1987.

Thank you for this comprehensive breakdown. As a neurology nurse, I see the impact daily. Early DMTs truly do change trajectories. I always tell my patients: your immune system didn’t fail you-it got misled. And science is teaching it the truth again. You’re not broken. You’re being repaired.

There’s a missing Oxford comma in the third paragraph. Also, 'myelin sheath' should be hyphenated as 'myelin-sheath' when used attributively. These details matter in medical communication.

Just wanted to add-my cousin in Mumbai started swimming 3x a week after diagnosis. Her EDSS score dropped from 4.5 to 2.0 in 18 months. Exercise isn’t optional-it’s medicine. And yes, the heat is a problem, but a fan and cold shower before? Game changer.

Coming from the UK, I’ve seen the NHS rollout of siponimod and ofatumumab transform lives. We’re not perfect, but we’re trying. The real win? Patients now live with MS, not just survive it. That shift-from terminal diagnosis to chronic condition-is the quiet revolution.

Neurofilament light chain testing? This is HUGE. I’ve been waiting for this. It’s like a smoke alarm for your nervous system-alerts you before the fire spreads. If your sNfL is above 15, it’s time to talk to your neurologist. No waiting for another relapse. Early action saves neurons.

Why are we still using outdated terms like 'lesions'? It’s dehumanizing. We’re talking about areas of active demyelination and axonal loss-not some abstract blotch on a scan. Language shapes perception. Let’s call it what it is: neural trauma. And stop calling it 'MS' like it’s a single disease. It’s a spectrum of immune betrayals.

So you’re telling me stress triggers flares… but we’re supposed to just ‘manage it’? Like that’s a fix? Meanwhile, people are working 60-hour weeks, juggling insurance battles, and paying $12,000 a month for meds. Tell me again how mindfulness is supposed to fix that.