For decades, proving that a generic drug works the same as the brand-name version meant testing it on people. Dozens of healthy volunteers, blood samples drawn every hour, weeks of clinical trials - all to show that the drug gets into the bloodstream the same way. It was expensive, slow, and sometimes unnecessary. Today, a smarter approach is changing that: IVIVC. It’s not magic. It’s science. And it’s replacing human testing for many drug formulations.

What Is IVIVC, Really?

IVIVC stands for In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation. In plain terms, it’s a mathematical link between how a drug dissolves in a lab dish and how it behaves inside the human body. If you can measure how fast a pill breaks down in a beaker with simulated stomach fluid, and that number reliably predicts how much drug enters the blood, you don’t need to test it on people. That’s the goal.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) first laid out the rules in 1996, but it took years for the industry to catch up. Today, IVIVC is the gold standard for getting regulatory approval without running full bioequivalence studies. It’s especially powerful for extended-release pills - the kind designed to release medicine slowly over 12 or 24 hours. For those, human testing is messy. The body absorbs the drug unevenly. But dissolution in a controlled lab setting? That’s repeatable. That’s measurable.

The Four Levels of IVIVC - And Why Level A Matters

Not all correlations are created equal. The FDA classifies IVIVC into four levels, and only one really unlocks a full biowaiver: Level A.

- Level A: This is the dream. It matches dissolution at every time point to blood concentration at every time point. Think of it like a perfect mirror - if the pill dissolves 40% at 2 hours, the blood level should be exactly what the model predicts. To qualify, the model must hit an R² value above 0.95, with a slope near 1.0 and an intercept near zero. It’s hard to build, but when it works, regulators accept it without hesitation.

- Level B: Uses averages - mean dissolution time versus mean residence time. Less precise. Doesn’t predict individual profiles. Not enough for a waiver on its own.

- Level C: Links one dissolution number (like % dissolved at 1 hour) to one blood parameter (like Cmax). Useful for quick checks, but doesn’t cover the full picture. Multiple Level C models can sometimes be accepted, but they’re risky.

- Multiple Level C: Several single-point relationships strung together. Easier to develop, but often fails when real-world conditions like food or stomach pH change.

For a true biowaiver - meaning no human testing required - regulators want Level A. It’s the only one that gives confidence the drug will behave consistently across populations. The FDA requires these models to predict AUC within ±10% and Cmax within ±15%. Miss that, and you’re back to square one: clinical trials.

Why Companies Chase IVIVC - The Cost of Skipping Human Trials

A single bioequivalence study costs between $500,000 and $2 million. It takes 3-6 months to run. You need 24-36 healthy volunteers. You need ethical approvals, monitoring, lab analysis, data cleaning. It’s a massive investment.

IVIVC, by contrast, saves time and money. One company reported that developing a Level A IVIVC for an extended-release oxycodone generic took 14 months and three formulation tries - but it saved them from running five separate bioequivalence studies. That’s roughly $8 million in avoided costs.

It’s not just about saving cash. It’s speed. A new generic can hit the market 6-12 months faster with IVIVC. That’s critical when patents expire and competition kicks in. For manufacturers, IVIVC isn’t a luxury - it’s a competitive advantage.

But It’s Not Easy - And Most Fail

Here’s the hard truth: 70% of IVIVC attempts fail. Why?

The biggest reason? Poorly designed dissolution tests. Many companies use the standard USP Apparatus 2 with plain water or buffer. That’s not enough. The stomach isn’t water. It has bile salts, enzymes, changing pH, food particles. If your test doesn’t mimic that, your model won’t predict real-life performance.

That’s where biorelevant dissolution comes in. It’s not fancy jargon - it’s science that uses simulated intestinal fluids with proper pH, bile salts, and enzymes. Studies from the University of Maryland show this method improves correlation accuracy by 40-60% for complex formulations. Yet, only 20% of early IVIVC submissions used it in 2020. By 2025, the American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists expects 75% to use it.

Another common failure? Not testing enough formulations. To build a strong model, you need at least three versions of the drug - fast-dissolving, slow-dissolving, and the target. You need to see how each behaves in vivo. Too many companies test only one or two. That’s like trying to predict a car’s fuel efficiency with only one speed. You won’t get it right.

And then there’s the expertise gap. Only about 15% of pharma companies have in-house IVIVC specialists. Most outsource to contract labs like Alturas Analytics or Pion, which report success rates of 60-70% when brought in early. Companies that wait until late-stage development? Their failure rate jumps to 80%.

When IVIVC Won’t Work - The Limits

IVIVC isn’t a universal fix. It fails for certain drugs:

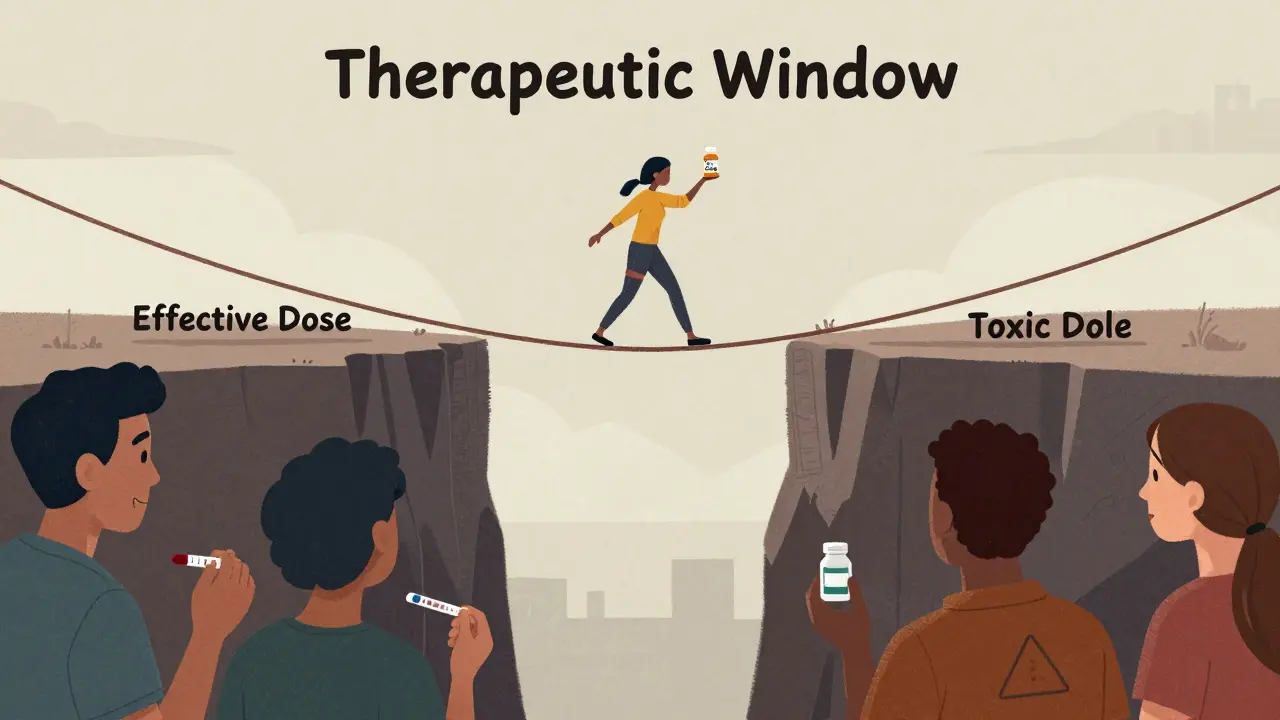

- Narrow therapeutic index drugs - like warfarin or lithium. Even tiny differences in absorption can be dangerous. Regulators won’t waive human testing here.

- Non-linear pharmacokinetics - where dose changes don’t scale predictably with blood levels.

- Drugs with complex absorption - like those absorbed in the colon or dependent on gut enzymes.

- Injectables, ophthalmics, implants - IVIVC for these is still experimental. The EMA and FDA are exploring it, but no formal waivers exist yet.

For immediate-release drugs, the simpler Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) often replaces IVIVC. If a drug is highly soluble and highly permeable (Class I), and the formulation is similar to the brand, you can skip human testing without IVIVC. But for extended-release, modified-release, or poorly soluble drugs? IVIVC is the only path.

Regulatory Trends - What’s Changing in 2025

Regulators aren’t standing still. The FDA’s 2023 review of 127 IVIVC submissions found that 64% failed because the dissolution method didn’t reflect real human conditions. That’s a wake-up call. The agency is now pushing for biorelevant methods as the new baseline.

They’ve also released draft guidance for IVIVC in topical products - creams, gels, patches - signaling this approach is expanding beyond pills. The EMA and FDA held a joint workshop in 2024 on machine learning models for IVIVC. AI can spot patterns in dissolution and pharmacokinetic data that humans miss. Early results look promising, but regulators demand transparency. No black boxes.

Approval rates are climbing. In 2018, only 15% of IVIVC submissions were accepted. By 2022, that jumped to 42%. The FDA’s GDUFA III plan allocates $15 million to improve IVIVC science over the next five years. Industry adoption is growing - but slowly. Only five of the top ten generic manufacturers have dedicated IVIVC teams. The rest are still catching up.

How to Get It Right

If you’re developing a complex generic, here’s what works:

- Start early - don’t wait until your final formulation. Begin IVIVC work during prototype development.

- Use biorelevant media - not just water. Include bile salts, enzymes, and pH gradients that mimic the GI tract.

- Test at least three formulations with different release rates. Cover the full spectrum.

- Collect dense pharmacokinetic data - at least 12 blood time points per subject, across multiple studies.

- Validate your model with an independent dataset. Don’t just use the same data you built it with.

- Work with experts. Hire a contract lab with proven success in Level A models.

It’s not cheap. It’s not fast. But when done right, it’s the most efficient way to get a generic drug to market without putting people at risk.

What’s Next?

By 2027, McKinsey & Company predicts IVIVC-supported biowaivers will make up 35-40% of all extended-release generic approvals - up from 22% in 2022. That’s not just growth. That’s a transformation.

IVIVC isn’t replacing in vivo testing because it’s easier. It’s replacing it because it’s smarter. It’s based on real science, not tradition. It reduces human exposure to unnecessary trials. It cuts costs without cutting corners. And it’s the future of generic drug development.

The challenge isn’t whether IVIVC works. It’s whether your team has the tools, the data, and the expertise to build it right. Because if you don’t - you’ll still be stuck running human studies in 2030.

What is the main purpose of IVIVC in generic drug development?

The main purpose of IVIVC is to predict how a drug will behave in the human body based solely on laboratory dissolution tests. This allows regulators to approve generic drugs without requiring expensive and time-consuming clinical trials involving human volunteers, as long as the model is scientifically validated.

Why is Level A IVIVC preferred over other levels for biowaivers?

Level A IVIVC provides a point-to-point correlation between dissolution and blood concentration at every time interval. This means it can predict the entire pharmacokinetic profile - not just one number like Cmax or AUC. Regulators trust Level A because it shows the drug behaves consistently across the full absorption window, making it the only level that reliably supports full biowaivers.

What are the biggest reasons IVIVC submissions get rejected by regulators?

The top reasons are: 1) dissolution methods that don’t reflect real human physiology (like using plain water instead of biorelevant fluids), 2) insufficient formulation variation (not testing enough versions of the drug), and 3) poor model validation (using the same data to build and test the model). About 64% of failed submissions in 2023 failed due to lack of physiological relevance.

Can IVIVC be used for all types of drugs?

No. IVIVC is most reliable for oral extended-release products. It generally doesn’t work for drugs with narrow therapeutic indexes (like warfarin), non-linear pharmacokinetics, or those absorbed in unusual ways. It’s also not yet accepted for injectables, ophthalmics, or implants, though research is ongoing.

How does biorelevant dissolution testing improve IVIVC success?

Biorelevant dissolution uses fluids that mimic the stomach and intestines - including bile salts, enzymes, and pH changes - instead of plain water or buffer. This gives a much more accurate picture of how the drug will dissolve and be absorbed in the body. Studies show it improves correlation accuracy by 40-60%, making models far more predictive and regulator-friendly.

Is IVIVC becoming more common in regulatory submissions?

Yes. From 2018 to 2022, IVIVC submissions increased by 35%, and approval rates rose from 15% to 42%. The FDA is actively encouraging it, allocating $15 million for research under GDUFA III. By 2025, biorelevant methods are expected to be standard in 75% of new IVIVC submissions, signaling a major shift in how generics are approved.

15 Comments

Level A IVIVC is the holy grail for a reason. When you nail that point-to-point correlation, you’re not just saving millions-you’re eliminating unnecessary human exposure to clinical trials. The FDA’s push for biorelevant media is long overdue. Water-based dissolution is a relic from the 90s. Bile salts, pH gradients, enzymes? That’s what the GI tract actually looks like. If your model doesn’t mirror that, you’re just guessing.

And honestly? The 70% failure rate isn’t surprising. Most companies treat IVIVC like a checkbox at the end of development. It’s not. It’s a core design tool. Start with it during prototyping, not after you’ve spent $2M on a failed BE study.

Stop pretending IVIVC is some revolutionary breakthrough. It’s just a way for Big Pharma to cut corners under the guise of science. You think regulators actually trust these models? They approve them because they’re understaffed and overworked. The FDA doesn’t have the manpower to run real BE studies for every generic. So they let companies self-certify with math that’s often gamed. Wake up. This isn’t progress-it’s regulatory capture.

Biorelevant dissolution? 😎 Obviously. But let’s be real-most CROs still use USP II with pH 6.8 buffer like it’s 2005. The real MVPs are the labs that use FaSSIF/FeSSIF with pancreatic enzymes. I mean, come on. If you’re not simulating the actual GI milieu, you’re just doing fancy dissolution spectroscopy. 🤷♂️

And yes, I’ve seen Level A models fail because someone used a single formulation. Like, dude. You need at least 3. Minimum. Or don’t bother submitting at all. #PharmaTwitter

It’s fascinating how much the field has evolved, really. When I first started in pharma analytics back in the early 2010s, IVIVC was still considered a niche academic exercise-something you’d see in a conference poster, not in an NDA. Now, it’s the backbone of generic approval for extended-release products. The shift toward biorelevant media has been transformative, and I’ve personally seen companies go from 80% failure rates to 70% success simply by switching dissolution media and collecting more time points.

But here’s the thing: even with all the advances, the human element still matters. The data needs to be interpreted by someone who understands not just the math, but the physiology behind it. A model with an R² of 0.98 means nothing if it was built on flawed in vivo data. Validation isn’t optional-it’s the difference between approval and rejection.

And let’s not forget the cost savings. One client of mine saved nearly $10M over three years by switching to IVIVC for three products. That’s not just efficiency-that’s accessibility. More generics mean lower prices, which means more patients get treated. That’s the real win.

Anyone else notice how often people forget that IVIVC doesn’t work for all drugs? Like, yeah, it’s awesome for extended-release oxycodone, but if you’re working on a narrow therapeutic index drug like warfarin, you’re still doing BE studies. No shortcuts there. And injectables? Still no dice. FDA’s been clear on that.

Also-biorelevant media is a game changer. I used to think it was overkill, but after seeing the data from a project last year? 50% better correlation. No joke. We switched from plain buffer to FaSSIF and suddenly our model went from ‘maybe’ to ‘approved.’

Still, gotta say, the expertise gap is real. So many companies outsource this and then act surprised when it fails. You need people who live in this space, not just a lab tech running assays.

so ivivc is basically like saying ‘if the pill dissolves the same in a cup, it’ll work the same in you’? kinda wild but also kinda genius? 😅

One thing I’d add to the list of best practices: don’t underestimate the importance of inter-lab reproducibility. I’ve seen brilliant Level A models get rejected because another lab couldn’t replicate the dissolution profile. It’s not enough to have a good model-you need a robust, transferable method.

Also, the FDA’s new focus on transparency in AI-driven IVIVC is a good sign. Black-box models have no place in regulatory science. If you’re using machine learning, you need to explain how the algorithm arrived at its conclusions. Otherwise, it’s just math magic-and regulators won’t buy it.

Let’s be honest-this whole IVIVC thing is just a distraction. Behind the scenes, the FDA is under pressure from big pharma to speed up approvals so they can make more money. They’re letting companies skip human trials because they’re scared of lawsuits if they delay generics. And now they’re pushing AI? Please. AI doesn’t know what a human stomach feels like. It just finds patterns in data that were manipulated to look good.

Remember when they said GMOs were safe? Now look at the health crisis. This is the same playbook. They call it ‘science,’ but it’s just corporate convenience dressed up in lab coats. Wake up. The real cost isn’t money-it’s patient safety.

Level A IVIVC? Yeah, it’s impressive. But let’s not pretend it’s foolproof. I’ve reviewed 12 submissions this year. Half of them had R² > 0.95… and still failed because the in vivo data was from 12 subjects in fasting state, and the product is meant for elderly patients with GI motility issues. You can’t model what you don’t measure.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘we used biorelevant media’ claims. Half the time, they used the wrong bile salt concentration. It’s not ‘biorelevant’ if you’re using 2 mM taurocholate and the human duodenum has 12 mM. This isn’t rocket science-it’s basic physiology. Why is this still so hard?

It is a matter of profound moral and scientific concern that we have allowed the reduction of human biological inquiry to a mere algorithmic approximation. The human body is not a variable in a regression model. To substitute the lived, dynamic, and irreducible complexity of physiological response with a dissolution curve is not progress-it is epistemological hubris. We are not merely approving drugs; we are eroding the very epistemic foundation of medical ethics. The FDA’s embrace of IVIVC as a panacea reflects a culture that values efficiency over dignity. This is not science. It is technocratic reductionism masquerading as innovation.

Oh, here we go again. Another ‘IVIVC saves money’ fairy tale. Let’s talk about the real cost: when a generic fails in the field because the model didn’t account for food effects. I’ve seen it. Patients get subtherapeutic doses. Then the lawsuits start. The company blames ‘variable GI transit.’ But the real problem? They used water-based dissolution and called it a day.

And now the FDA’s pushing AI? Great. So now we’re trusting neural nets to predict whether a pill will work in a diabetic with gastroparesis? You’re not saving money-you’re creating a time bomb. And someone’s gonna die because you wanted to skip 36 healthy volunteers.

Really appreciate this breakdown. I’ve worked on a few IVIVC projects and the difference between a good model and a great one is all in the details. One thing I’ll add: don’t just validate with one dataset. Test it against real-world patient data-like from electronic health records. That’s where you find the blind spots.

Also, shoutout to the labs that are actually using biorelevant media. It’s still rare, but when you see it, you know. The correlation just… clicks. And yeah, starting early is key. We waited till Phase 3 once. Lost 18 months. Never again.

Big fan of the Level A breakdown. One thing I’d emphasize: the slope and intercept aren’t just statistical checkboxes. A slope of 0.92 and intercept of 1.5 might look ‘close’-but if your model predicts 15% higher Cmax than reality, that’s a clinical risk. It’s not about hitting 0.95 R²-it’s about being clinically accurate.

Also, the FDA’s new draft guidance for topical IVIVC? Huge. Transdermal patches are a nightmare for BE studies. If we can get this right for gels and creams, we could eliminate hundreds of unnecessary human trials every year.

Hey, if you’re thinking about building an IVIVC model, don’t go it alone. Find someone who’s done this before. I’ve seen too many teams spend six months on a model only to realize they didn’t test enough formulations. Three is the minimum-but five is better. And yes, biorelevant media is non-negotiable.

Also, if you’re outsourcing, ask for their success rate on Level A. If they don’t know it, walk away. This isn’t a commodity service-it’s a science partnership.

Replying to @5575: You’re right that failures happen in the field-but that’s why we validate with independent datasets and test under fed/fasting conditions. The problem isn’t IVIVC. It’s poor execution. The same thing happens in BE studies when you use the wrong food matrix or don’t account for circadian variation.

IVIVC isn’t a magic bullet. But it’s the best tool we have. And when done right, it’s safer than BE studies because you’re testing *more* conditions, not fewer. We run 8 dissolution profiles across 4 pH levels and 3 media types. BE studies? One food condition. One time point. That’s the real risk.