Recovery Timeline Estimator for Medication-Induced Nasal Congestion

How long will it take you to recover?

Enter when you stopped using nasal decongestant sprays and your treatment plan to estimate your recovery timeline.

Your Recovery Timeline

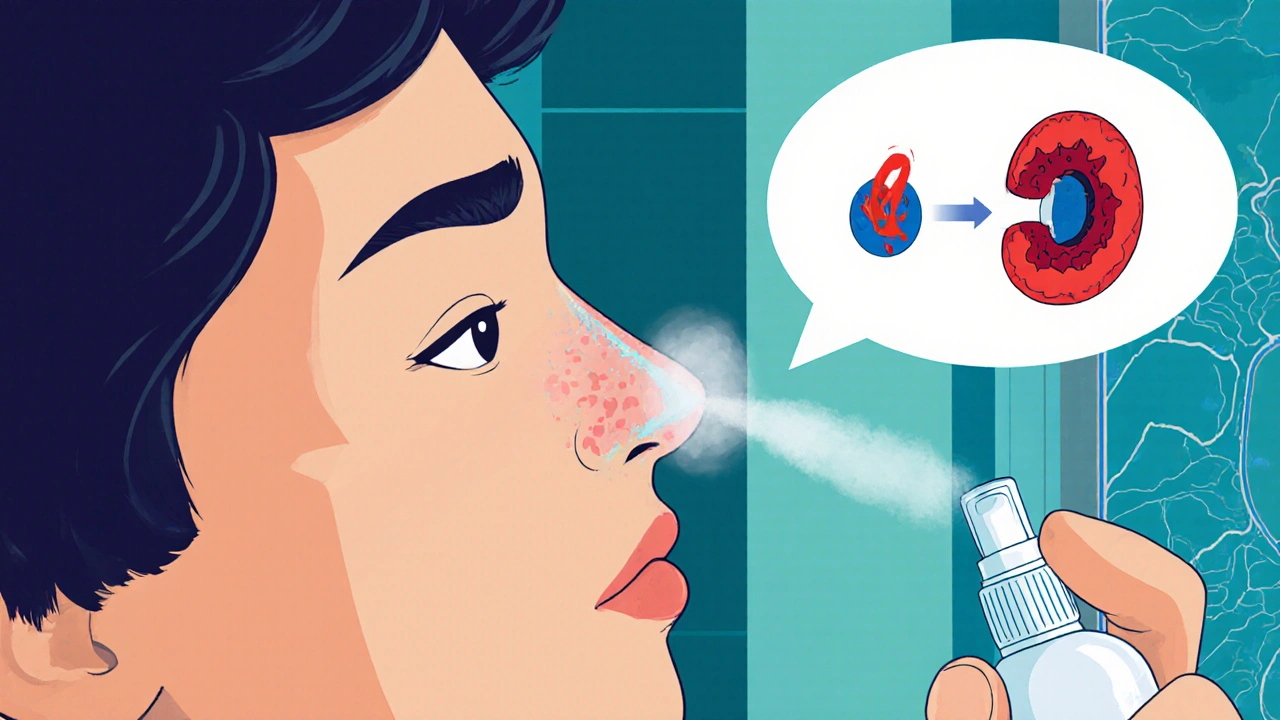

Ever reached for a nasal spray, felt the relief, and then wondered why the stuffiness came back even stronger? That’s the classic pattern of medication‑induced nasal congestion, medically known as Rhinitis medicamentosa - a rebound inflammation caused by overusing topical decongestants.

What Triggers Rebound Congestion?

Most over‑the‑counter sprays contain powerful vasoconstrictors that shrink the blood vessels in your nasal lining. The three culprits responsible for the majority of cases are:

- Oxymetazoline (found in products like Afrin)

- Phenylephrine (common in rapid‑relief sprays)

- Xylometazoline (used in many European brands)

When you apply these agents for more than three-four days, the vessels rebound-dilating instead of staying tight. The result is a cycle of worsening blockage that pushes you to spray more.

How to Spot the Condition Early

Typical red flags include:

- Persistent congestion that doesn’t improve with a second dose

- Little or no clear‑runny discharge (rhinorrhea)

- Swollen, pale, or gritty‑looking nasal mucosa on examination

- Dry mouth, snoring, or oral breathing, especially at night

According to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), about 10 % of users who exceed the recommended spray duration develop some degree of rebound congestion.

First‑Line Management: Stop the Spray

All leading otolaryngology societies agree: the cornerstone of treatment is stopping the offending decongestant.

Two practical ways to do this are:

- One‑nostril‑at‑a‑time method - recommended by the Mayo Clinic. You discontinue the spray in the more congested nostril first, allowing that side to clear before tackling the other.

- Gradual taper - advocated by the Cleveland Clinic. Reduce the number of sprays per day over a week before quitting completely.

Both approaches aim to minimize the dreaded “withdrawal week” when symptoms feel worst.

Adjunctive Therapies to Ease Withdrawal

While the spray is being phased out, several supportive treatments can accelerate recovery.

Intranasal Corticosteroids

These are the most evidence‑backed option. Agents like Mometasone furoate (Nasonex) and Fluticasone propionate (Flonase) reduce inflammation and have shown 68‑75 % symptom reduction after 2‑4 weeks of twice‑daily use.

Oral Corticosteroids

In severe cases, a short course of prednisone (0.5 mg/kg for five days) can break the rebound loop quickly. A 2021 multicenter trial reported an 82 % success rate, but doctors reserve this for patients who can’t tolerate intranasal sprays.

Saline Nasal Irrigation

Simple salt‑water rinses help clear mucus and keep the lining moist. Systematic reviews cite a 60 % improvement rate, especially when done two to three times daily during the first week of withdrawal.

Capsaicin Nasal Spray

Emerging data from the European Rhinologic Society show a 55 % efficacy in reducing congestion, likely by desensitizing nasal sensory nerves. It’s an option if steroids are contraindicated.

Putting It All Together: A Practical 14‑Day Plan

The following schedule blends the best‑practice steps from Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, and the American Academy of Otolaryngology‑Head and Neck Surgery (AAO‑HNSF).

| Day(s) | Action | Supportive Treatment | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1‑3 | Stop spray in the most congested nostril (or begin taper) | Saline irrigation every 2 h, optional oral prednisone if severe | Peak congestion, possible dry mouth |

| 4‑7 | Discontinue spray in the second nostril (or continue taper) | Start intranasal corticosteroid twice daily, continue saline | Gradual relief, reduced swelling |

| 8‑10 | No decongestant use | Intranasal corticosteroid once daily, consider capsaicin spray if needed | Noticeable opening of nasal passages |

| 11‑14 | Maintain nasal hygiene | Continue corticosteroid at maintenance dose, saline as needed | Near‑complete resolution, prevention of relapse |

Adherence matters: studies show a 92 % success rate when patients follow the full 14‑day protocol versus 63 % when they quit abruptly.

Prevention: How to Use Nasal Sprays Safely

Even the best treatment plan can’t rescue you from repeated misuse. Follow these simple rules:

- Limit use to no more than 3-4 consecutive days. The NHS recommends a maximum of one week, but the shorter the better.

- Stick to the recommended dose (usually 1-2 sprays per nostril, 2-4 times daily).

- Read the label for warnings about hypertension or MAO‑inhibitor interactions.

- Consider saline irrigation as first‑line relief for colds or allergies before reaching for a decongestant.

Public health data indicate that only 28 % of OTC buyers receive proper usage instructions-a gap that contributes to an estimated $1.2 billion in annual U.S. healthcare costs.

When to Seek Professional Help

If congestion persists beyond two weeks after stopping the spray, or if you notice any of the following, schedule an ENT appointment:

- Recurring nosebleeds or crusting that won’t heal

- Development of polyps (seen in up to 15 % of chronic users)

- Severe headaches or facial pain that could signal sinus infection

An ENT can perform a nasal endoscopy, confirm the diagnosis, and tailor a medication plan-sometimes incorporating allergy testing or surgery for chronic cases.

Future Directions: New Therapies on the Horizon

Researchers are testing several novel agents:

- Nasal antihistamine sprays (e.g., azelastine) showed 65 % efficacy in early 2023 trials at Johns Hopkins.

- Low‑dose capsaicin protocols are in phase 2 studies at Massachusetts Eye and Ear, reporting up to 70 % symptom relief.

- Long‑acting intranasal phosphodiesterase inhibitors are being explored for “resetting” vascular tone without steroid side effects.

While promising, these options remain experimental. Until they’re widely available, the tried‑and‑true combination of spray cessation, steroids, and saline remains the gold standard.

Key Takeaways

- Rhinitis medicamentosa is a reversible condition caused by overusing vasoconstrictive nasal sprays.

- Stop the offending spray-preferably using the one‑nostril‑at‑a‑time or taper method.

- Support withdrawal with intranasal corticosteroids, saline irrigation, and, if needed, a brief course of oral steroids.

- Follow a structured 14‑day plan for the best chance of full recovery.

- Prevent future episodes by limiting spray use to a few days and using saline first.

How long does rebound congestion last after stopping a nasal spray?

Most people experience the worst symptoms during the first 3‑7 days. By the end of the second week, many report significant relief, especially if they use intranasal steroids and saline rinses.

Can I use a different nasal spray while I’m weaning off the first one?

Switching to another vasoconstrictive spray defeats the purpose and often worsens the rebound. Opt for saline or a steroid spray instead.

Are oral decongestants safer than nasal sprays?

Oral agents like pseudoephedrine avoid local rebound but can raise blood pressure. They’re not risk‑free, especially for people with hypertension.

What’s the best way to clean my nose with saline?

Use a sterile, isotonic solution (0.9 % NaCl) in a squeeze bottle or neti pot. Tilt your head forward, breathe through the mouth, and irrigate each nostril for 30‑60 seconds. Do this 2‑3 times a day during withdrawal.

When should I see an ENT specialist?

If congestion persists beyond two weeks after stopping the spray, if you develop nosebleeds, crusting, or suspect nasal polyps, or if you have severe facial pain, book an appointment. Early evaluation improves outcomes.

12 Comments

When you treat a simple nasal spray like a miracle drug you betray the very principle of moderation, and that betrayal manifests as rebound congestion with ruthless clarity. The vasoconstrictor, while powerful, is a double‑edged sword that punishes you for ignoring the three‑day rule. You think you’re winning a battle against a cold, yet you’re actually enlisting a hidden enemy that attacks the nasal lining. Every extra spray compounds the vascular fatigue, and the tissue responds by dilating beyond its baseline. This is not a myth, it is a physiological cascade that has been documented in countless ENT studies. The moment you abandon restraint, the mucosa enters a state of hyper‑reactivity that feels like a siege. Your breathing becomes a chore, not a privilege, and the frustration you feel is a direct result of your own decisions. The recommended one‑nostril‑at‑a‑time method is not a suggestion, it is a mandate for anyone who respects their own health. You must confront the habit with the same vigor you used to conquer the original congestion. Tapering is a strategic retreat, a controlled withdrawal that prevents the catastrophic rebound. Saline irrigation is a humble ally, washing away the inflammatory remnants while you rebuild vascular tone. Intranasal corticosteroids are the frontline troops that suppress the inflammation you have provoked. If you neglect these steps, the rebound will persist for weeks, turning a short‑term fix into a chronic nuisance. Do not be fooled by the convenience of a quick spray; the long‑term cost is far higher. Take responsibility now, or you will pay the price in endless sniffles and sleepless nights.

Stopping the spray is the first step and you can do it without drama. Use saline rinses a few times a day to keep the lining moist. Start an intranasal steroid like fluticasone after the first two days of withdrawal. Most people see noticeable improvement by day ten. Stick to the plan and you’ll be breathing easy again.

In the grand tapestry of human physiology, the nasal mucosa, delicate and responsive, becomes a battlefield when we over‑indulge in decongestants, a paradox of relief and ruin, a dance of vasoconstriction and dilation. One might argue, with a sigh of resignation, that the very act of seeking comfort, however fleeting, sows the seeds of future discomfort, a lesson echoed in ancient wisdom, that excess breeds deficiency. The rebound phenomenon, therefore, is not merely a medical curiosity, but a profound reminder, a mirror reflecting our impatience, our desire for instant gratification, and the inevitable price we must pay. Clinical trials, numerous and rigorous, have demonstrated, beyond doubt, that tapering, saline irrigation, and corticosteroids, when applied judiciously, restore balance, a harmony once shattered by reckless usage. Moreover, the psychological component, subtle yet significant, cannot be ignored, for the mind, entwined with the body, amplifies the perception of congestion, creating a feedback loop that perpetuates the cycle. So, when you contemplate another spray, pause, reflect, and consider the cascade of consequences, which extend far beyond the fleeting sensation of a cleared nostril. Ultimately, wisdom lies in restraint, in listening to the body’s quiet signals, and in embracing holistic, evidence‑based strategies.

Corrine makes a good point about the psychological side-people often feel trapped by the urge to spray again. A practical tip is to set a timer for each nostril, limiting yourself to the recommended days. Combining that with a gentle saline rinse can calm the irritation while you wean off. I’ve seen patients recover faster when they keep a symptom diary, tracking when the worst congestion hits. That awareness helps break the mental loop that drives overuse.

Yo man stop pressin da spray quick, its a trap. The vasoconstrictr is like a ninja that com back bigger. Use salt water rinse a few times a day, it help clean the stuff. Also try a steroid spray like fluticasone after a couple days off. Trust me it work if u stick to it.

😂👍 Yeah, the water rinse is a game‑changer! Keep it gentle and you’ll feel the difference fast. Also, don’t forget to drink plenty of fluids, it helps thin the mucus. If you still feel stuffy, a low‑dose steroid can calm the inflammation. Stay strong, you got this! 🌟

I totally get how frustrating rebound congestion can be-especially when you just want relief. Remember that the body needs time to reset, so be patient with the process. Saline irrigation and a steady steroid routine are your best friends right now. If you notice any bleeding or severe pain, reach out to an ENT sooner rather than later. You’re not alone in this, many have walked the same path and come out breathing easier.

yeah i felt the same lol. i tried the one-nostril thing and it kinda helped. the steroid spray is kinda harsh tho but i used it every other day and it cleared up. just dont overdo the spray man, stick to the plan. 👍

If you’re still pushing a decongestant after the recommended window, you’re basically sabotaging your own airway. Cut it off immediately, then grab a saline bottle and start irrigating every few hours. Add a twice‑daily intranasal corticosteroid like mometasone and you’ll see a rapid drop in swelling. For severe cases, a short burst of oral prednisone can break the cycle in 48 hours-just make sure you’re not hypertensive. The key is discipline: no more sprays, no excuses.

Buddy you dont realize the pharma compnies design these sprays to keep you addicted, its all part of a larger agenda to control the popluation. they load the vasoconstrictors with hidden chemicals that mess with your body long term, while the docss say its just a "rebound". if you think oral steroids are safe, think again-they're a gateway to bigger health programs. stay woke, read the fine print, and trust natural remedies over the big pharma hype.

Stop the spray, use saline, and let steroids do the work.

The information is clear: overuse leads to rebound, cessation is essential, and supportive treatments speed recovery. Follow the steps, avoid shortcuts, and you will regain normal breathing.