Immunosuppression Infection Risk Estimator

Assess Your Infection Risk

Select your immunosuppression type to see the most common infections, key symptoms, and testing recommendations.

When your immune system is turned down-whether by steroids, chemotherapy, or transplant drugs-you don’t just get sick more often. You get sick in ways most people never see. Infections that barely make a ripple in healthy people can turn deadly in seconds for someone on immunosuppressants. And here’s the scary part: you might not even feel sick until it’s too late.

Why Normal Infections Become Unusual

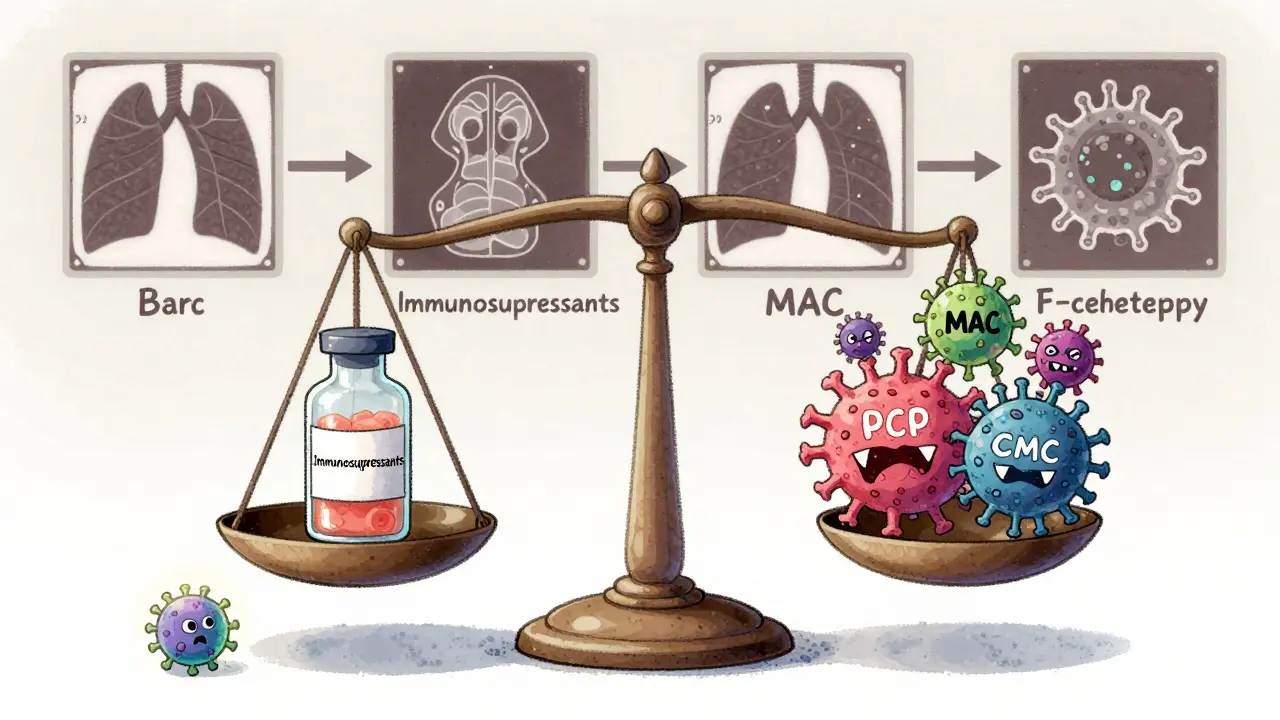

In a healthy person, a cold is a cold. A cough, a runny nose, maybe a day off work. But in someone on long-term steroids or after a kidney transplant, that same cough could be Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia-PCP for short. It’s not rare in immunosuppressed patients. In fact, it’s the most common infection found in kids with immune disorders before a stem cell transplant, showing up in over 20% of lung samples tested. This fungus doesn’t usually cause trouble in people with normal immunity. But when T-cells are suppressed, it spreads fast through the lungs. And unlike in healthy people, there’s no fever. No chills. No obvious signs. One study found that nearly a quarter of infected children showed zero symptoms, even when the infection was severe enough to be caught on a lung scan. The same goes for Aspergillus, a mold you breathe in every day. In healthy people, it’s harmless. In someone with low white blood cells, it can grow into a life-threatening lung infection. Mortality? Over 50% even with the best antifungal drugs. Compare that to 15% in people with normal immune systems. That’s not just worse-it’s a different disease entirely.Who Gets What? Immune Defects and Their Signature Infections

Not all immunosuppression is the same. The type of drug, the reason for it, and which part of the immune system is affected all determine what kind of infection you’re at risk for. If your body can’t make antibodies-like in X-linked agammaglobulinemia-you’re wide open to Giardia intestinalis. This tiny parasite doesn’t just cause diarrhea. In immunosuppressed people, it causes chronic, smelly, bloated stomachs, and weight loss. In one study, 87% of affected children had these symptoms. Standard treatment? Metronidazole. But in these patients, it often fails. Up to 40% need second-line drugs like tinidazole or nitazoxanide because their bodies can’t clear the bug on their own. If your T-cells are down-common after organ transplants or in people on high-dose steroids-you’re at risk for viruses that normally stay asleep. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivates in up to 40% of transplant patients without preventive treatment. It doesn’t just cause fever. It can wreck your lungs, liver, or gut. And because your immune system can’t fight back, the virus keeps multiplying. Some patients shed CMV for months, not days. Then there’s Mycobacterium avium (MAC). It’s everywhere-in soil, water, even tap water. Healthy people ignore it. But if your T-cells are gone, MAC can spread through your blood, infecting your liver, spleen, and bones. It’s slow, silent, and deadly. One study found 38% of babies with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) got MAC before they even got a bone marrow transplant. And if your white blood cells can’t kill bacteria-like in chronic granulomatous disease-you get strange abscesses. Not just in the skin. In the liver. In the spleen. Inside them? Live bacteria, hidden from antibiotics because your body can’t build the right walls to trap them.

When Symptoms Disappear

This is the trickiest part. In healthy people, infection means fever, redness, swelling, pus. In immunosuppressed patients? None of that. Often, nothing. One case from 1967 still haunts doctors today. A patient on immunosuppressants got what looked like a bad skin rash-red, inflamed, like erysipelas. It wasn’t. It was histoplasmosis, a fungal infection that usually shows up as tiny lung nodules. But without immune cells to react, it didn’t form the usual bumps. It just spread, like a wildfire with no firefighters. The patient died. That’s why doctors don’t wait for symptoms. They test. Routine bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) in high-risk patients finds pathogens in 37% of cases-even when the patient feels fine. A simple sputum test catches 65% of PCP cases. BAL catches 92%. So if you’re on immunosuppressants and have a cough, even a mild one, you get a lung scan. And a BAL. No waiting.Emerging Threats and New Realities

The last few years changed everything. The pandemic didn’t just bring COVID. It showed us how long viruses can live in immunosuppressed bodies. While healthy people clear SARS-CoV-2 in 10-14 days, some transplant patients shed the virus for over 120 days. That’s four months of being contagious, of the virus mutating inside them, of new variants brewing in one person. And it’s not just SARS-CoV-2. New coronaviruses-NL63 and HKU1-are now routine findings in lung samples from immunocompromised patients. They used to be footnotes. Now they’re on guidelines. In the 2022-2023 season, they made up 8.5% of respiratory infections in leukemia patients. Even the treatment landscape is shifting. Instead of just throwing antibiotics at the problem, doctors are starting to use pathogen-specific T-cell therapies. These are custom-made immune cells, grown in a lab from the patient’s own blood, trained to hunt down CMV or adenovirus. In trials, they worked in 70% of cases where drugs failed.

What You Need to Know If You’re on Immunosuppressants

If you’re on steroids, biologics, or post-transplant drugs, here’s what matters:- Don’t wait for symptoms. Fever isn’t always there. Redness isn’t always visible. If you feel off-even a little-get checked.

- Know your risks. Are you antibody-deficient? Then watch for Giardia. T-cell suppressed? Watch for CMV, PCP, and fungi. Neutropenic? Watch for Aspergillus and Pseudomonas.

- Get tested regularly. Routine lung scans, stool tests, blood cultures. These aren’t optional. They’re lifesavers.

- Treatment isn’t one-size-fits-all. What works for a healthy person might not work for you. Doses need adjusting. Drugs need combining. Failure rates are higher. Don’t assume standard treatment is enough.

- Ask about new options. T-cell therapy isn’t available everywhere yet-but it’s coming fast. Ask your infectious disease specialist if you’re a candidate.

The Hard Truth

Despite all the advances-better drugs, smarter testing, targeted therapies-infection-related death rates in transplant patients still hover around 25-30%. That hasn’t changed in a decade. Why? Because the immune system isn’t just a shield. It’s a whole network. And when you turn it down, you don’t just lose one defense. You lose them all. The goal isn’t to avoid every germ. That’s impossible. The goal is to catch the dangerous ones early-before they spread, before they silence your body’s warning signs, before it’s too late. You’re not just managing a disease. You’re managing a fragile balance. And the smallest symptom could be the loudest alarm you’ll ever hear.Can steroids cause unusual infections?

Yes. Long-term steroid use suppresses key parts of the immune system, especially T-cells and macrophages. This opens the door to opportunistic infections like Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, histoplasmosis, and cryptococcosis-organisms that rarely cause disease in healthy people. Steroids also mask fever and inflammation, making infections harder to detect until they’re advanced.

What are the most dangerous infections for immunosuppressed patients?

The most dangerous are those that exploit specific immune gaps: Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (for T-cell deficiency), Aspergillus (for neutropenia), CMV (for T-cell suppression), Giardia (for antibody deficiency), and Mycobacterium avium complex (for severe combined immunodeficiency). These infections have high mortality rates-up to 50% for Aspergillus-even with treatment.

Why don’t immunosuppressed patients get a fever when infected?

Fever is triggered by immune signals like cytokines. When the immune system is suppressed-especially the cells that produce these signals-the body can’t mount a normal inflammatory response. So even severe infections may show no fever, no redness, no swelling. This is why doctors rely on lab tests, not symptoms, to diagnose infections in these patients.

How are unusual infections diagnosed in immunosuppressed patients?

Diagnosis relies on aggressive testing. For lung infections, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) is the gold standard-it detects Pneumocystis with 92% accuracy. For gut parasites like Giardia, stool tests with immunofluorescent antibodies are 98% sensitive. Blood cultures, PCR tests for viruses, and imaging like CT scans are routine. Culture-negative cases may require metagenomic next-generation sequencing to find unknown pathogens.

Can you prevent infections if you’re on immunosuppressants?

Yes, but prevention is layered. Prophylactic antibiotics (like trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for PCP), antivirals (like valganciclovir for CMV), and antifungals are common. Vaccinations before starting immunosuppression matter-flu, pneumococcal, hepatitis B. Avoiding raw foods, moldy environments, and crowded places during high-risk periods helps. But no prevention is 100%. Regular monitoring and early testing are just as important.

13 Comments

Man, I never realized how wild this stuff is until my cousin went through a transplant. He was just coughing a little, thought it was allergies-turns out it was PCP. No fever, no nothing. Scared the hell out of us. Doctors were like, 'We test everyone like this now.' Honestly, if you're on immunosuppressants, don't wait for symptoms. Just get checked. Period.

Oh wow, so now we’re supposed to be terrified of every speck of dust and tap water? Next they’ll tell us to wear a hazmat suit to the grocery store. I mean, really? My grandma’s 80, never had a transplant, and she still eats raw cookie dough. She’s fine. Maybe we just need to chill and stop medicalizing normal life.

This is an exceptionally well-structured and clinically nuanced exposition on the intersection of immunosuppression and opportunistic pathogens. The delineation between humoral and cellular immune deficiencies, paired with pathogen-specific risk stratification, represents a paradigm shift in clinical vigilance. One must acknowledge the profound implications for preventive medicine, particularly in the context of targeted T-cell therapies, which herald a new epoch in personalized infectious disease management.

Of course the medical establishment wants you to panic. More tests = more bills. More scans = more revenue. They’re not telling you that 90% of these ‘unusual infections’ are overblown because they don’t want to admit how much they overprescribe steroids and transplant drugs in the first place. Wake up, people. Your body can handle a little fungus. They just want your insurance to pay for another round of expensive ‘prophylaxis’.

It’s funny how we treat the immune system like a switch-on or off. But it’s not. It’s a symphony. And when you mute one instrument, the whole piece collapses. We don’t just lose defenses-we lose context. The body doesn’t scream when it’s dying. It just… stops singing. And we’re too busy looking for fever to notice the silence.

It is imperative to underscore the critical importance of proactive surveillance in immunocompromised populations. The absence of classical inflammatory markers does not equate to the absence of pathogenic burden. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), coupled with multiplex PCR and metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS), constitutes the current diagnostic gold standard. Moreover, serial monitoring of CD4+ T-cell counts and serum galactomannan levels remains indispensable in high-risk cohorts.

Everyone’s acting like this is new info. Newsflash: we’ve known this since the 80s. But hospitals still don’t screen routinely because it’s expensive and inconvenient. And guess who pays? The patients. I’ve seen people die because their doctor said, 'Wait and see.' No. Stop waiting. Test. Now. And if your doctor won’t, find one who will. This isn’t optional-it’s survival.

My sister’s on tacrolimus after her liver transplant. She doesn’t even get colds anymore-she just gets tested every 3 months. It’s a weird life, but it works. I used to think it was overkill. Now I get it. It’s not about being paranoid. It’s about being smart. And honestly? It’s kind of empowering. You learn your body’s quiet signals.

THEY’RE HIDING THE TRUTH!!! Why is CMV shedding for 120 days NOT on the news?!?!? This is a BIO-WEAPON waiting to happen!!! They’re letting people walk around for MONTHS infecting others with mutated viruses!!! And they call it ‘immunosuppression’? No-it’s a COVER-UP!!! I’ve seen the documents!!! The CDC knows!!!

My dad’s a transplant guy. He’s been on meds for 12 years. He doesn’t go to big crowds, he avoids compost piles, and he washes his hands like he’s in an OR. But he also laughs a lot, cooks weird food, and plays guitar. This isn’t about fear. It’s about adapting. You don’t have to live in a bubble-you just have to know where the edges are.

From a philosophical standpoint, the immunosuppressed individual occupies a liminal space between biological vulnerability and technological augmentation. The medical interventions employed-prophylaxis, T-cell therapy, genomic sequencing-represent not merely therapeutic measures, but epistemological extensions of the self. The body, once autonomous, now relies upon algorithmic vigilance. This transformation redefines personhood: we are no longer merely patients, but nodes in a network of predictive immunology.

Wait… so you’re telling me the government and Big Pharma are using immunosuppressants to make people more vulnerable so they can test new bioweapons under the guise of ‘transplant care’? That’s why they push steroids so hard! And the ‘new coronaviruses’? Totally engineered. They’re testing airborne variants in real time on immunocompromised people. Look at the timing-right after the pandemic. Coincidence? I think not.

Look, I get it-you’re trying to be helpful. But honestly? Most people on immunosuppressants just want to live, not be lectured about BALs and mNGS. You’re not helping by making them feel like walking petri dishes. Just tell them: ‘If you feel off, call your doctor. Don’t Google it. Don’t panic. Just call.’ That’s all they need.