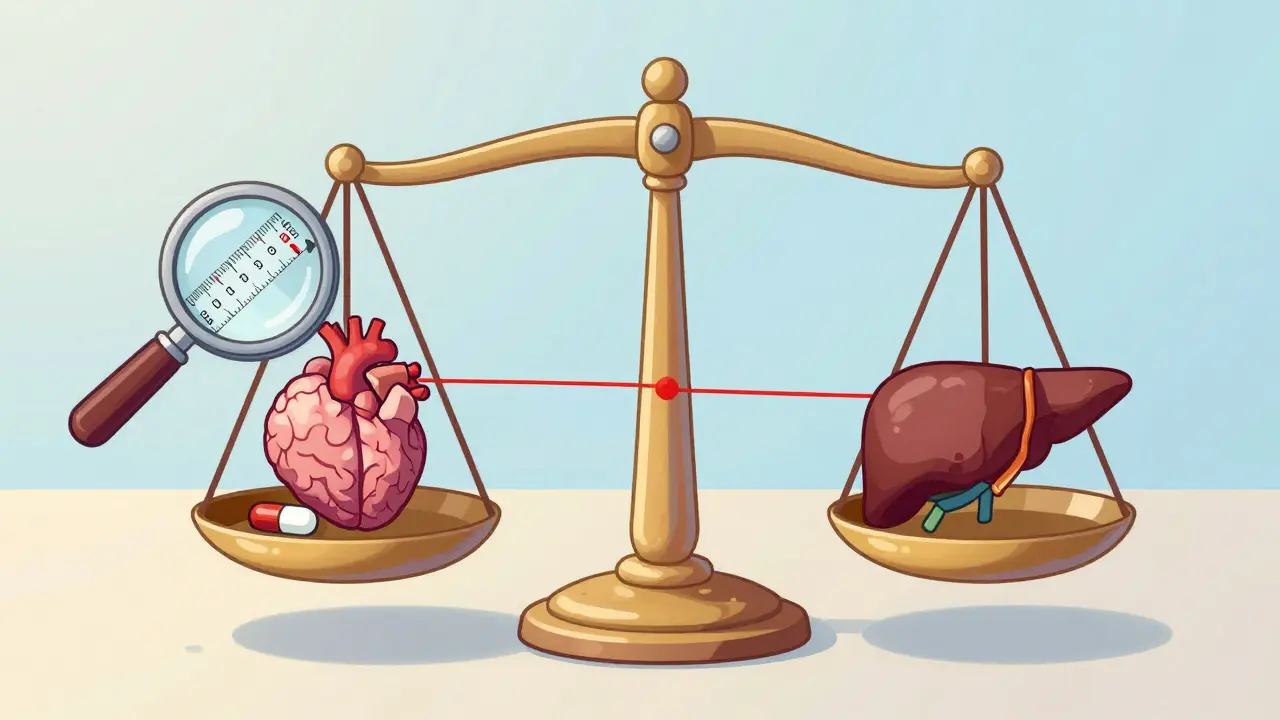

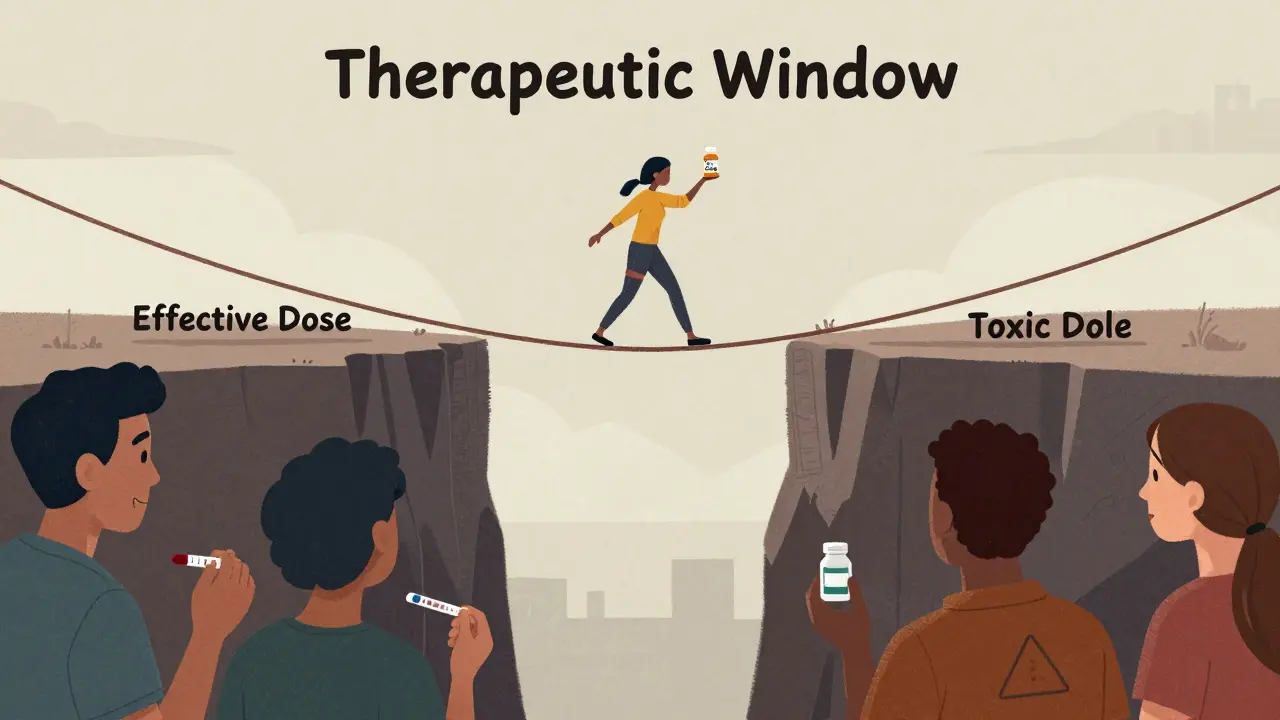

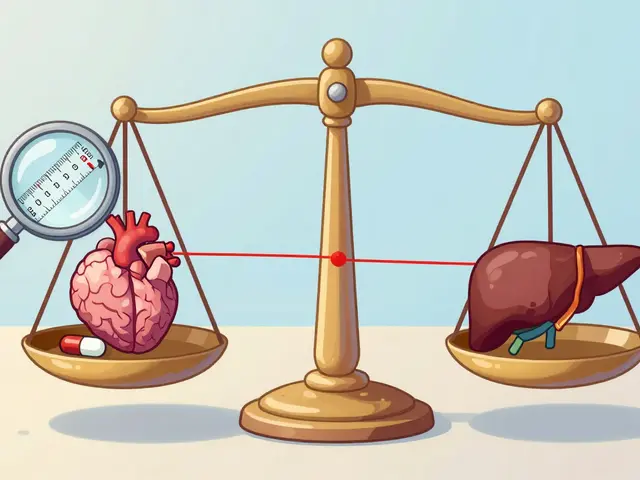

When a drug has a narrow therapeutic index, even tiny changes in how much of it enters your bloodstream can mean the difference between healing you and harming you. That’s why the FDA treats these medications differently than your average pill. For drugs like warfarin, phenytoin, or tacrolimus, the margin between a safe dose and a dangerous one is razor-thin. A 10% variation in blood levels? That might be fine for an antibiotic. For an NTI drug, it could trigger seizures, organ rejection, or dangerous bleeding. This isn’t theoretical - it’s life-or-death chemistry.

What Makes a Drug an NTI Drug?

The FDA doesn’t just guess which drugs are dangerous. They use hard numbers. Since 2022, the agency has defined a narrow therapeutic index (NTI) as a drug with a therapeutic index of 3 or less. That means the lowest dose that causes toxicity is no more than three times the lowest dose that works. For example, if a drug starts working at 1 mg per liter of blood and becomes toxic at 3 mg/L, it’s an NTI drug. If it works at 1 mg/L and becomes toxic at 5 mg/L? It’s not. Simple. Clear. Measurable.

Drugs that meet this threshold include carbamazepine, digoxin, everolimus, lithium carbonate, phenytoin, valproic acid, and warfarin. These aren’t random picks. They’re medications where doctors routinely monitor blood levels. You’ve probably heard of therapeutic drug monitoring - that’s the red flag. If a doctor checks your blood for a drug regularly, chances are it’s an NTI drug.

But here’s the catch: the FDA doesn’t publish a full list. Instead, they embed the NTI designation into product-specific guidance documents for each generic version. So if you’re trying to find out whether a drug is an NTI, you need to look at the FDA’s guidance for that exact generic product, not a general list.

How Bioequivalence Standards Differ for NTI Drugs

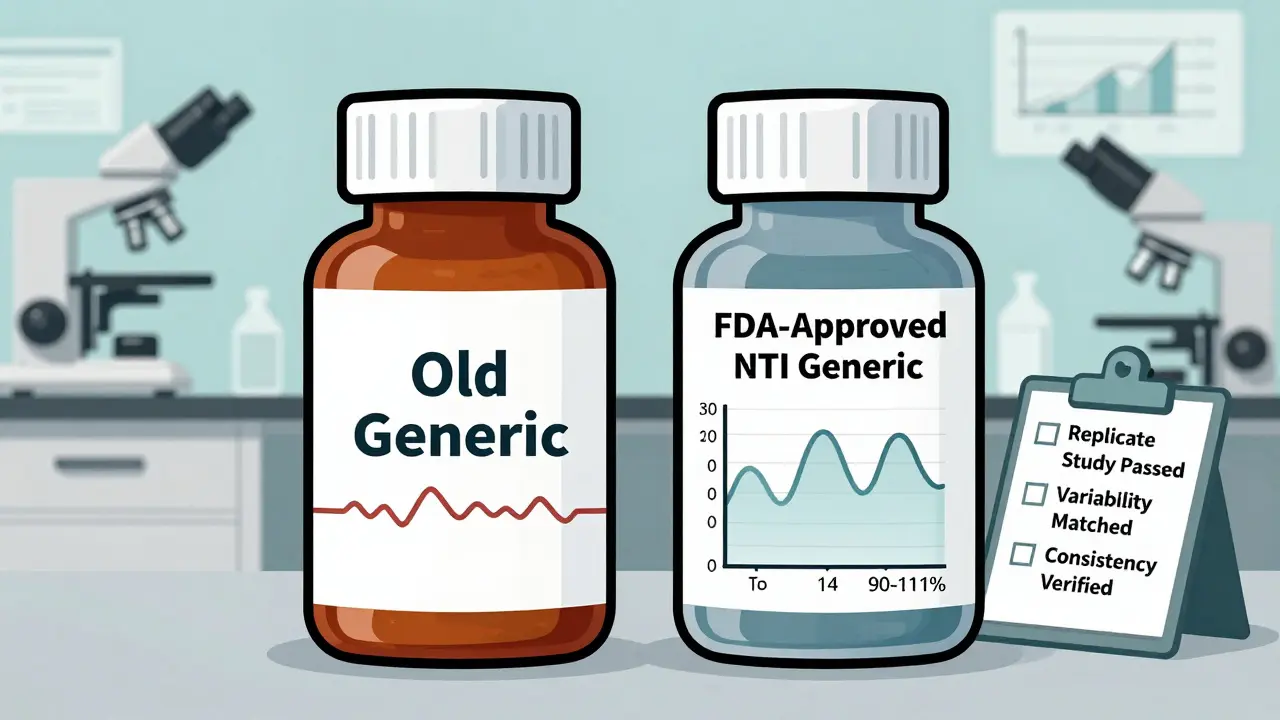

For most generic drugs, the FDA says they’re bioequivalent if their blood concentration falls between 80% and 125% of the brand-name drug. That’s a 45% window. For NTI drugs? That’s way too wide. The FDA tightened it to 90% to 111.11% - a 21% window. That’s a 53% reduction in allowable variation.

But it’s not just about the range. The FDA uses a two-part test. First, the generic must pass the standard 80-125% bioequivalence limits. Second, it must also pass the tighter 90-111% limits. That’s not optional. Both must be met. And there’s more: the study must be a replicate design. That means each patient takes both the brand and generic versions multiple times - not just once. This gives the FDA a much clearer picture of how consistent the drug is from dose to dose.

Why does this matter? Because NTI drugs aren’t just about average exposure. They’re about consistency. A drug that averages out to the same level over time might still swing wildly between doses. For a patient on warfarin, that swing could mean a clot one day and a stroke the next. The FDA’s replicate studies catch those spikes and dips.

There’s also a variability check. The FDA looks at how much the drug’s concentration varies within a single person. If the brand-name drug has high variability (more than 21% within-subject variability), the limits can be scaled - but only if the generic matches the brand’s variability exactly. For NTI drugs, the upper limit of this variability ratio must be 2.5 or less. In plain terms: the generic can’t be more unpredictable than the brand.

Why the FDA Didn’t Just Lower the Limits

You might wonder: why not just say all NTI drugs need 90-111%? Why the complexity? The answer is biology. Some NTI drugs naturally vary a lot in how they’re absorbed. If the FDA forced every drug into a fixed 90-111% range, some safe generics might be blocked just because they’re slightly more variable - not because they’re unsafe.

The FDA’s scaled approach lets them be smart. If a brand-name drug has low variability, the generic must match it tightly. If the brand has higher variability, the generic can have a little more wiggle room - but only if it’s as variable as the original. This protects patients without blocking good generics.

Compare this to Europe or Canada. They use fixed limits - no scaling. The FDA’s method is more precise. It’s based on real data from the brand drug, not a one-size-fits-all number.

Real-World Evidence vs. Theoretical Concerns

There’s a lot of fear around NTI drugs. Some doctors won’t switch patients from brand to generic. Some pharmacists refuse to substitute. Some states even require signed consent before switching. But here’s what the data says: when generics meet the FDA’s stricter NTI standards, they perform just as well as the brand.

Studies on tacrolimus - a critical drug for transplant patients - show that multiple generic versions, all approved under NTI standards, are bioequivalent to each other. Patients on these generics had stable blood levels and no increased risk of rejection. The same holds true for phenytoin and digoxin. Real-world data from hospitals and clinics don’t show spikes in adverse events after switching.

So why the fear? Partly because of old studies. A few early generic versions of antiepileptic drugs didn’t meet today’s standards. Those were pulled. But today’s generics are held to a higher bar. The lingering doubt comes from old headlines, not current science.

The FDA’s position is clear: generic NTI drugs approved under these rules are therapeutically equivalent. They’re not just “close enough.” They’re proven to be interchangeable. The agency points to over 15% of newly approved generics in 2022 being NTI drugs - and none have shown safety issues post-approval.

What This Means for Patients and Prescribers

If you’re on a drug like warfarin or lithium, you might be worried about switching to a generic. You’re not alone. But if your generic was approved after 2022, it went through the toughest testing any generic drug can face. The FDA didn’t just check the average. It checked consistency, variability, and performance across multiple doses. That’s more than most brand-name drugs undergo.

Prescribers should know: if the generic is labeled as meeting NTI standards, it’s safe to substitute. The FDA doesn’t require special consent or monitoring beyond what’s already standard for the drug. If your doctor is hesitant, ask: “Was this generic approved under the FDA’s NTI bioequivalence guidelines?” If yes, the answer is yes.

Pharmacists, too, should feel confident. The FDA’s standards are designed to eliminate the risk of substitution failure. The tighter limits, replicate studies, and variability controls aren’t red tape - they’re patient protection.

What’s Next?

The FDA is working to align its NTI standards with global regulators. Right now, Europe, Canada, and the U.S. all have different rules. That creates confusion for manufacturers and patients alike. Harmonizing these standards is a priority - not just for efficiency, but for safety.

Researchers are also studying how to better identify NTI drugs. The current threshold - therapeutic index ≤ 3 - works for most. But what about drugs where toxicity isn’t clearly defined? Or drugs with complex metabolism? The FDA is exploring new models, including machine learning tools that analyze clinical outcomes, not just blood levels.

One thing won’t change: the FDA’s commitment to safety. For NTI drugs, there’s no room for compromise. The standards are strict. The testing is rigorous. And the goal is simple: make sure every pill, no matter the brand, does exactly what it’s supposed to - without risk.

Are all generic drugs held to the same bioequivalence standards as NTI drugs?

No. Only drugs classified as Narrow Therapeutic Index (NTI) are held to stricter standards. Most generic drugs must show bioequivalence within 80-125% of the brand-name drug. NTI drugs must meet a tighter 90-111% range and pass additional tests for variability and consistency. This extra layer of scrutiny applies only to medications where small changes in concentration can cause serious harm.

How does the FDA decide which drugs are NTI drugs?

The FDA uses a pharmacometric model based on data from clinical studies. A drug is classified as NTI if its therapeutic index - the ratio between the minimum toxic dose and the minimum effective dose - is 3 or less. The agency also considers whether the drug requires routine blood monitoring, if doses are adjusted in small increments, and whether its concentration range in the body is narrow. These criteria help identify drugs where even minor differences in absorption or metabolism could be dangerous.

Can I trust a generic NTI drug as much as the brand-name version?

Yes, if it’s FDA-approved under the NTI guidelines. The FDA requires replicate bioequivalence studies, tighter limits (90-111%), and proof that the generic matches the brand’s variability. Real-world data from transplant centers, epilepsy clinics, and anticoagulation services show no increase in adverse events when patients switch to approved generic NTI drugs. The agency confirms these generics are therapeutically equivalent and safe to substitute.

Why do some doctors still refuse to prescribe generic NTI drugs?

Some doctors base their hesitation on outdated studies from the early 2000s, when generic quality was inconsistent. Today’s standards are far stricter. The FDA’s current NTI requirements - introduced after 2010 and refined in 2022 - ensure that today’s generics are as reliable as the brand. However, misinformation and lingering patient concerns persist, especially around drugs like phenytoin and warfarin. Education and access to current data are key to changing practice.

Do all countries use the same NTI bioequivalence standards as the FDA?

No. The FDA uses a scaled approach that adjusts limits based on the brand drug’s variability. The EMA (Europe) and Health Canada use fixed limits - typically 90-111% - without scaling. This can make it harder for manufacturers to get approval in multiple regions. The FDA is pushing for global harmonization, but differences remain. A generic approved in the U.S. under NTI rules may not automatically qualify in Europe, and vice versa.